One of the more common things I see folks get confused on is the rank structure of the Navy and the jobs sailors held. While the Army and the Marines have some commonality in rank titles and insignia, the Navy (with exception to the Coast Guard) is its own sea creature. Many of the names and titles associated with Navy jobs are based on tradition and heavily influenced by new technology. In an effort to make this an easier reference, I am focusing on the enlisted side of things in the WWII-era as there is plenty on this topic alone to explain… and get confued about.

Terms To Know.

First, I need to clarify some terms up that you will need to know so you have a better understanding going forward.

- Rating – This is a sailor’s specialty in the Navy. Think of this like the modern MOS system in other services. Sailors who have a rating are considered “rated men.”

- Rate – For the lay person, think of rate as rank. But, officially and still true today, officers in the Navy have rank and the enlisted have rates.

- Paygrade – This is the level of pay a sailor made. Unlike today, paygrades did not necessarily correlate to rate and varied by rating. Paygrades were numbered with the 1st paygrade being the highest in pay.

- Nonrated – A sailor without a specialty rating, usually within the first three paygrades. Sometimes referred to as unrated.

- Striking – The process of an unrated sailor learning a rating through on-the-job training. A sailor in this program is considered a ‘striker.’

- Branch – Navy specialties during WWII were grouped into seven branches: Seaman, Engine Room Force, Artificer, Aviation, Special, Commissary, and Messman & Steward. A sort of eighth branch for Specialists was temporarily created for specialties not covered by current rates to meet wartime needs.

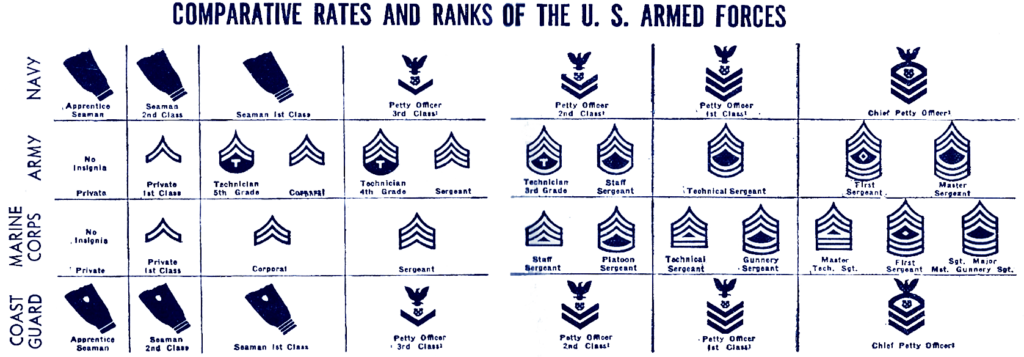

Let’s start by going over the basic structure of Navy rates. Below is an illustration of rates and ranks pulled from the Bluejackets’ Manual of 1944.

Looking at that chart, things look pretty straight forward, right? Well… hold fast! Things are about to get confusing.

Pay Grades.

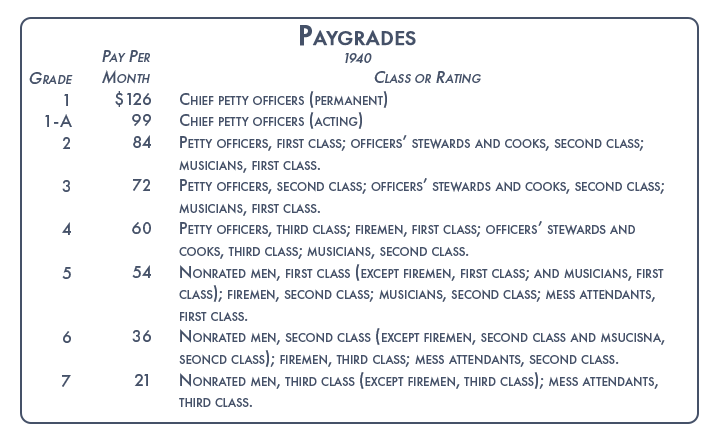

Going off the chart above, each column would represent a grade, which translates to pay… hence pay grade. You can see that there are seven columns but there were technically eight enlisted paygrades at this time when you include the Acting or Appointed Chief Petty Officer Pay Grade. As you can see in the chart below, paygrades were not standardized in regards to the ‘nonrated’ sailors at the start of the war.

One thing to remember is that pay grades are just simply that: grades of pay. They are not good indicators of authority as some jobs were set higher in pay grade due to their technical or physical difficulty. During the period between 1940 and the end of 1943, a seaman 2c and a fireman 2c were technically at the same level of authority but they were not paid equally. This was to meant to compensate the fireman’s more technical job. An unrated fireman 1c could be paid the same as a petty officer 3c and musician 1c could be paid the same as a petty officer 2c!

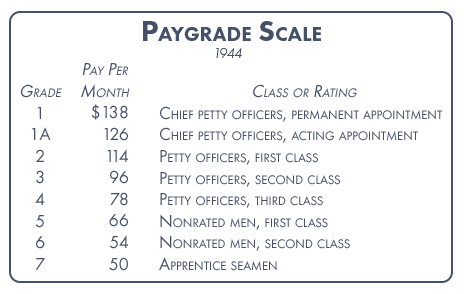

Obviously, this is very confusing to us… and the Navy must have thought the same because on January 1, 1944, pay grades were standardized across the board:

You will notice that in both pay grade charts, there are two levels for chief petty officer: permanent and acting. In order to meet the wartime demands in manpower but not blow the budget, acting appointments were given. These appointments were temporary and essentially for the duration of the war. To make an acting appointment permanent, the chief would have to apply and be recommended by leadership. Approval was proponent to there being a need for his rate by the Navy. If this wasn’t possible, then the sailor would revert to a rate more applicable to his experience and time in service, but this wasn’t an issue until after the war.

Navy Enlisted Branches

Okay, we now see the framework of how the enlisted sailors were structured by rate. Let’s take a look at how they were trained and employed. The entire enlisted force was divided up by seven different branches. Each branch is comprised of related specialties with their own training pipelines. These branches were Seaman, Artificer, Engine Room Force, Special, Commissary, Aviation and Messman (later renamed Steward). Technically, the Engine Room Force was a part of the Artificer branch, but is often listed autonomously. An eighth branch was established for new Specialist ratings created during the wartime emergency in order to fill crucial roles which did not fall within the other branches.

The Seaman branch comprised of what sailors today call ‘topside’ ratings, such as Gunner’s Mates and Boatswain’s Mates. The Artificer branch included ratings that repaired or manufactured things, such as Carpenter’s Mates and Painters, but also included other technical rates like Radiomen and Radarmen. The Engine Room Force was filled with rates specifically related to the operation engines and machinery that kept the fleet powered and moving. The Special branch included support ratings, such as Pharmacist’s Mates, Yeomen and Storekeepers. Commissary branch specifically comprised of food service for the crew, whereas the Messman/Steward branch was focused solely on officer’s wardroom support. The Aviation branch is, of course, focused on the handling of aircraft, but do know that Photographer’s Mates were also a part of this section because the Navy initially used photographers for air reconnaissance. Lastly, the Specialist branch covers every other odd-end technical rating created during the war that didn’t quite fit within the other existing ratings. Overall, a few ratings did shift from one place to another, but the majority of them stayed in the same branch throughout the war.

Rated vs. Nonrated

Let’s clarify what it means to be ‘rated,’ or to have a rating. Ratings are job specialties such as Boatswain’s Mate, Gunner’s Mate, Water Tender, etc. Those who qualified in a rating are considered “rated” and, conversely, those without ratings are considered “nonrated” or “unrated.” Simply put, all petty officers have ratings and are thus rated; there are no nonrated petty officers. One way that helped me remember this is to think of a vehicle: one that has been “rated” with a safety “rating” is better than one without; the higher its “rate” of speed, the quicker you’ll get to where you want to go (more pay and career retirement).

There are seven nonrated grades: Seaman, Fireman, Hospital Apprentice, Bugler, Musician and Mess Attendant (later renamed Steward’s Mate in 1943). The nonrated grade for every branch and rating was Seaman with the following exceptions: Firemen were assigned to the Engine Room Force only, Hospital Apprentice was the nonrated class specific to the Pharmacist’s Mate rating. For the musical ratings, the nonrated Buglers progressed to become Buglemasters while Musicians followed their own rating structure. This later changed in 1944 when Bugler denoted the nonrated grade for both Buglemaster and Musician ratings. Mess Attendants and Steward’s Mates were specific to the Messman/Steward branch ratings.

Though these are not ratings, they do have rates of 3rd, 2nd and 1st class. You’ll sometimes see reference to sailors being ‘rated’ or hold ‘ratings’ in these categories, such as “this man is rated Seaman 2nd Class” or “he held a rating of Bugler 1st Class.” Also, while it’s safe to assume that anyone below Petty Officer 3rd Class is nonrated, there is sometimes an exception to this rule and which I will describe later.

There are three avenues in which a sailor can become rated: by completing a service school, through a direct appointment, or by ‘striking’ for a rate once they’re in the fleet. Determining which path a sailor took all began with the Classification Interview.

The Classification Interview.

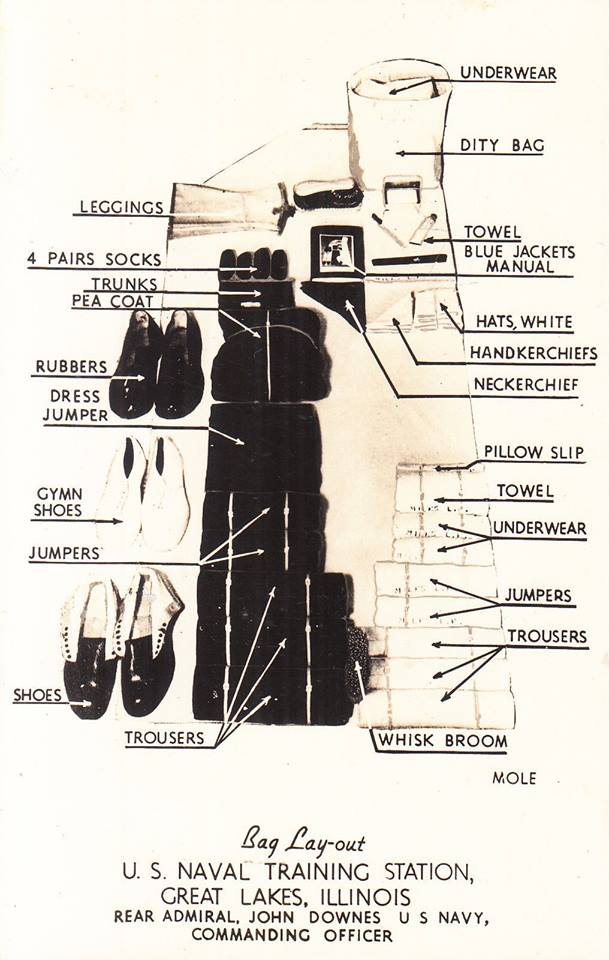

Every enlisted sailor during WWII entered the Navy as an Apprentice Seaman (AS), the lowest in the eight wartime pay grades. Upon arrival at a Naval Training Station (aka, boot camp) a physical screening was conducted to see if the recruit met Navy standards, which had stricter standards than the induction center’s physical screening. Each recruit would take a written exam and would meet with a classification interviewer usually within the first two weeks. This person would then determine how America’s newest sailor would be trained in order to meet the needs of the Navy.

The classification interviewer (which was also a rating: Specialist C) basically defined your service. He would take in consideration the recruit’s exam scores, his physical screening results, previous education, and prior work experience as well consider his personal interests, and would then determine if the sailor would go on to further training after boot camp. If the sailor was not a good match for any service schools, or the need for personnel in the fleet were too immediate, the sailor would be directly assigned to a command shortly after graduation from recruit training. Though there were minimum scores listed for each rating or school, some flexibility was given to the interviewer to waive lower scores if an overall impression was made that the sailor would be still be a good fit for a specific rating. The interviewer had a lot of influence on the kind of Navy experience a sailor was going to have based on very cursory information and one’s first impression.

Interviewers also had authority to directly apply ratings to qualifying sailors. Those with civilian education and work experience that translated well to in-demand ratings were sometimes automatically rated right within boot camp in order to rapidly fill those vacancies. In one example, letters home from a recruit at Naval Training Station Farragut revealed how he was happy that he was being rated as a Yeoman 3rd Class because of his ability to type was even assigned duties in the station’s legal office while still in recruit training. I had met a teacher many years ago who had served during the war. After his interview, it was determined his education and teaching background was experience enough to warrant him to be rated as an Athletic Instructor (Specialist A) and he was subsequently assigned to Naval Training Center San Diego to teach recruits. But because it didn’t make sense for a third class petty officer to be instructing recruits, he was given an acting appointment of chief petty officer to give him more authority.

So, in summary, an Apprentice Seaman in boot camp could expect three things: be sent to a school for further training based on how well his exams and interview went, be rated right off the bat based on his prior civilian experience, or be directly assigned to the fleet as an nonrated seaman. Deck work aboard ship was tough work but vital to keep a ship operational, and the nonrated sailors of the Seaman branch filled that need. It involved line handling, standing watches, corrosion prevention and basic seamanship. But, once there, a sailor still had one last option to try for a rating and that was through a process called striking.

Striking.

While at his command, an unrated sailor could request on-the-job training in a specific rating he is interested in, which is called striking. If accepted, the striker would be assigned to a division in which the rated sailors there can train, mentor and assign him duties to learn their specialty. Training had as much practical application as possible along with classroom education and study groups. His progress was monitored by an officer and usually had a timeline for completion. Once he is ready, the sailor is called before an Examining Board consisting of three officers and is graded. Results are then forwarded to the Commanding Officer and, if satisfactory, the sailor is rated and advanced to petty officer third class.

Those looking to strike had to meet several prerequisites, such as having a minimum length of service, good evaluation marks, and be recommended by the commanding officer. There also needed to be a vacancy in that rating, at least within the command. Usually, sailors were in the 5th pay grade (so, Seaman 1c, Fireman 1c, etc) but sometimes the training can begin while they’re in the 6th pay grade. The striking program still exists today as the Professional Apprentice Career Track (PACT), but is much more focused in one of three branch pipelines (Seaman, Airman and Fireman) and with a clearer timeline for progression into a rating.

As I had mentioned earlier on, there are some exceptions or anomalies to sailors below petty officer third class being considered having a rating. Sometimes a striker would complete the qualifications and exam, and subsequently rated by the Commanding Officer, but there wasn’t a vacancy in that rate within the fleet yet. In such a case, the sailor was essentially considered rated and could do the work, but would have to wait until billets opened up in order to advance. When this happened, the sailor would then add the new rating in parenthesis when written out, such as S2c(SM) or F1c(MM). However, there was no change in title when they were addressed in person. This is essentially the process known as frocking: authorizing sailors to assume the job and responsibility of the next grade but won’t be paid until their official advancement as determined by time in grade and billet vacancy.

Other Confusing Things

Now that most of that is as clear as mud, I’d like to cover other aspects of confusion. One of these is when the term rated is sometimes used in official documentation to refer to the rate of a nonrated sailor. For example, a document may refer to a sailor as rated a Seaman 2nd Class. But, Seaman is not a rating, thus this sailor is unrated. In such cases, they are simply referring to the rate, aka rank, of that sailor. The same can be seen for Fireman, Bugler, Hospital Apprentice and Musician – all are not ratings, and thus considered nonrated, but are still rated in 3rd, 2nd and 1st class. NAVPERS 16138 “Naval Orientation” even points out on page 40 the confusing terminology.

For the musical side, things are way more complicated. Prior to January 1, 1944, Musician (Mus) and Bugler (Bug) were not linear and even skipped a whole paygrade. Musician 2c started at the same paygrade as a Seaman 1c, there was no 3rd class petty officer spot, and Musician 1c was paid the same as a petty officer 2nd class (paygrade 3). If promoted beyond that, their title changed to First Musician and was visibly denoted by a petty officer 1st class insignia. For the Chief spot, they would be labeled as Bandmaster… which is kind of a rad title. For Buglers, things were slightly offset as well, except Bugler 2c and Bugler 1c matched that of S2c and S1c. It also skipped the 3rd class P.O. grade and started with the label Buglemaster 2nd Class (Bgmstr2c) and then on up the chain to Chief Buglemaster (CBgmstr).

Another detail that makes things difficult to understand is that some ratings didn’t have the same linear progression in grades as others did prior to the standardization changes made in January of ’44. Looking at the Patternmaker (PM), the rating did not have a 3rd Class or Chief rate. Instead, it used the Carpenter’s Mate (CM) rates for those grades. So, for example, the path of advancement for a career Patternmaker prior to 1944 would be in this order: CM3c, PM2c, PM1c, CCM. There were also a few ratings that did not have anything below 1st class petty officer, such as Turret Captain. Aviation Pilot (AP) was similar, except the AP2c was only retained for disciplinary purposes.

Some rates had different name changes during the war. Soundman was created in 1942 (and only in 3rd and 2nd class) and was later changed to Sonarman in 1944. Also, there was no BM3c during this time period. The title for the third class petty officer of this rating was Coxswain (Cox).

You’ll sometimes see reference to a Seaman 3rd Class (S3c), which would be the same as Apprentice Seaman. However, this changed in 1944 and the S3c was dropped with most Apprentice Seamen advancing to S2c once ready.

Summary.

With all information, it’s pretty obvious as to why folks get confused and why I see a lot of misinterpretations in represented in media and living history. On top of the titles and terminology, what time frame can sometimes have an effect. As with anything, it is best to do specific research on the rating you’re focused on, and I hope to make that learning process easier for you.

I will cover the insignia for enlisted uniforms relating to Navy jobs and will also dive deeper into each rating in future posts. Please leave a comment on what rating is your favorite and what you’d like to see first, and be sure to subscribe to get updated when a new post is released!

Bibliography.

- Naval Orientation, NAVPERS 16138 Revised. (1945). Standards and Curriculum Division, Training, Bureau of Naval Personnel.

- Manual of Navy Enlisted Job Classifications, NAVPERS 15105. (1945). Bureau of Naval Personnel.

- Bluejackets’ Manual, 10th Edition. (1940). U.S. Naval Institute.

- Bluejackets’ Manual, 11th Edition. (1943). U.S. Naval Institute.

- Bluejackets’ Manual, 12th Edition. (1944). U.S. Naval Institute.

- U.S. Navy Uniforms and Insignia, 1940-1942. (2007 Sept. 20). Warner, Jeff. Schiffer Publishing

- Uniform-Reference.Net: Illustrated military insignia and uniform reference. (2018). www.uniform-reference.net. Broderick, Justin T.

- The Bluejacket’s Manual. (2021). www.bluejacketsmanual.com